Tracks, Traces & Other Fossils of The Grand Canyon & Grand Staircase

.

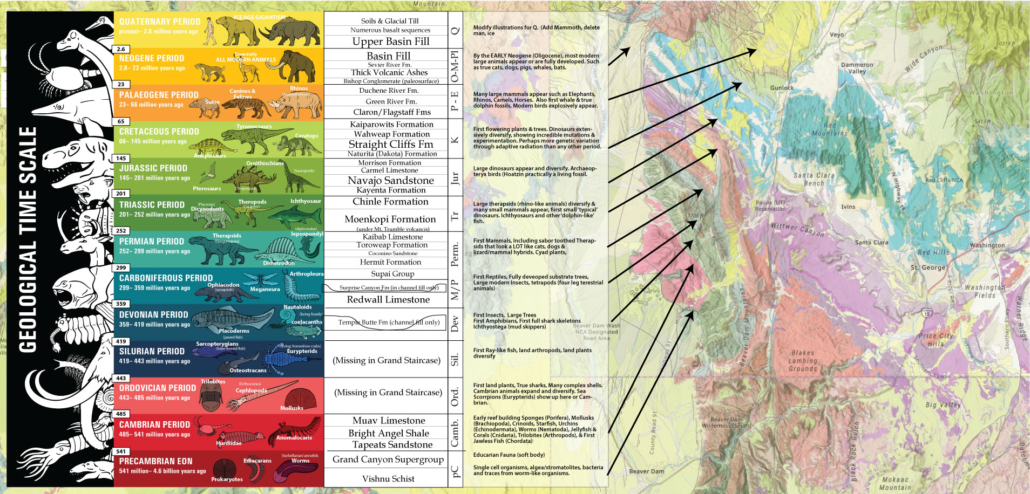

The Grand Canyon, a mile-deep chasm carved through millennia of Earth’s history, is not merely a spectacle of layered rock; it is a profound archive of ancient life. Within its vibrant strata, beyond the skeletal remains, lie the subtle yet powerful narratives of behavior etched in stone: tracksites and trace fossils. These ichnological treasures, from the uppermost Kaibab Formation down to the basal Tapeats Sandstone, offer unique insights into the locomotion, feeding, dwelling, and resting habits of creatures that roamed these ancient landscapes. This post descends through the Grand Canyon’s formations, highlighting the known track sites and trace fossils that whisper tales of life across vast stretches of time. For many more Grand Canyon region fossil picture, be sure to check out http://www.schursastrophotography.com/. Another fantastic resource is the Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument Paleo Resource Inventory.

A second purpose for this article is help point the many young-earth creationists I run up against understand why a catastrophic or ‘flood’ deposition of the layers of the Grand Canyon is entirely implausible. Not only does almost every layer in the canyon have fossils and track sites showing fairly uniformitarian principles existed at their deposition, but time anomalous layer around the world have evidences such as fossilized “IN PLACE” forests spanning at least from the Mississippian to Permian ages.

.

Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian)

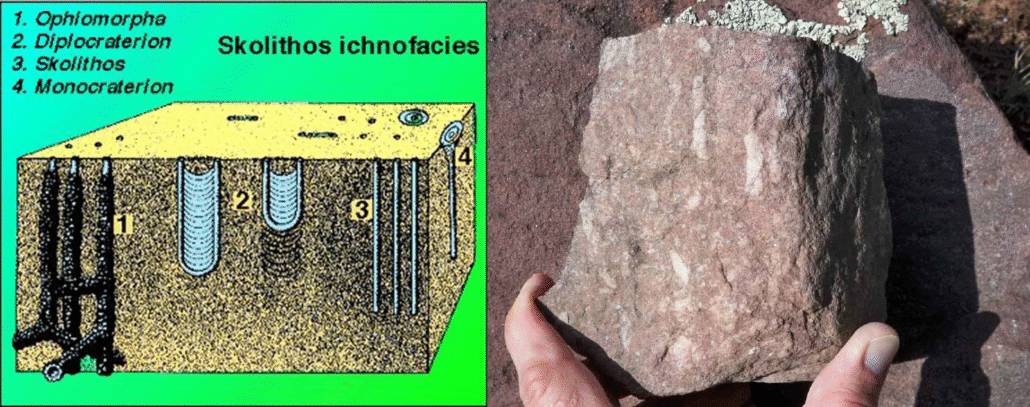

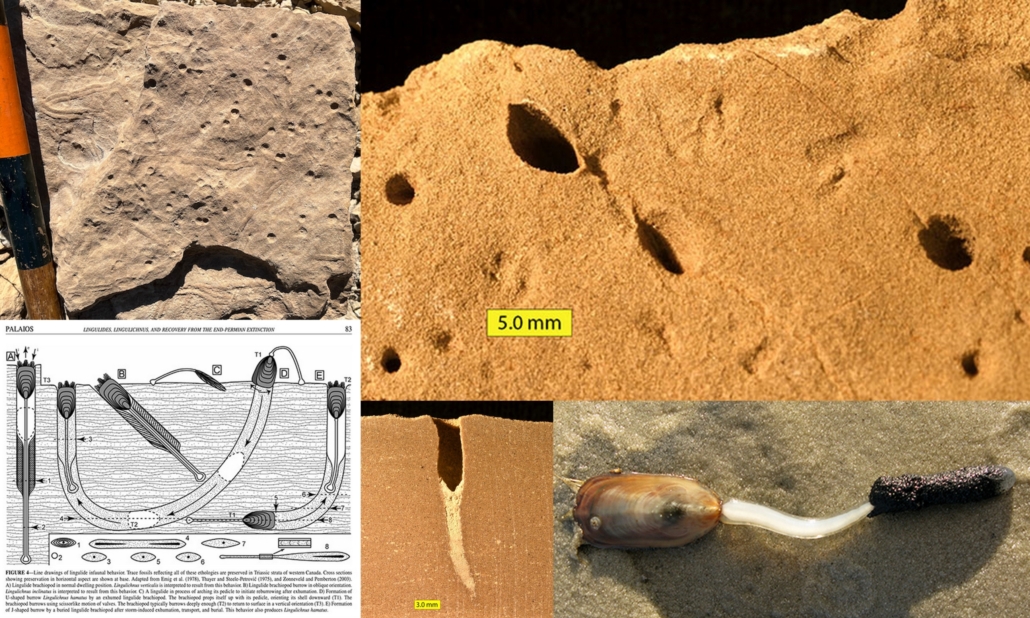

Finally, at the base of the Grand Canyon sequence lies the Tapeats Sandstone (Cambrian), a resistant sandstone deposited in a nearshore marine environment as the ancient sea transgressed across the continent. The Tapeats is characterized by abundant vertical burrows of suspension-feeding worms (Skolithos). These simple, tube-like structures are a hallmark of the “pipe rock” facies and represent one of the earliest widespread records of complex animal behavior in the fossil record. Horizontal trackways and burrows of other early invertebrates are also found, indicating the initial colonization of the shallow marine environment by mobile organisms. The Tapeats Sandstone marks the dawn of the Cambrian explosion in this iconic geological section.

.

Bright Angel Shale (Cambrian)

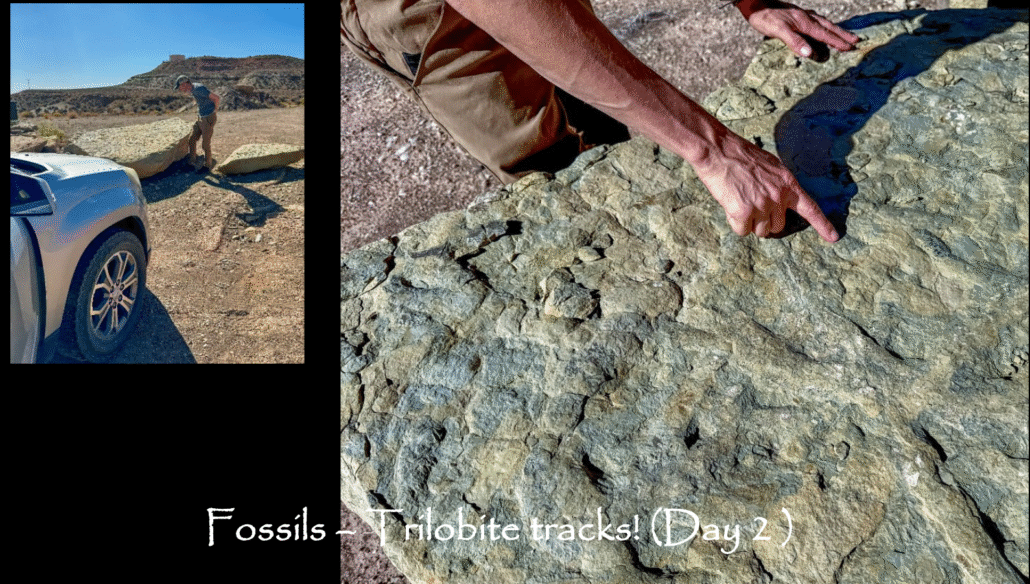

The Bright Angel Shale (Cambrian), a slope-forming unit composed of shale and siltstone deposited in a shallow marine setting, contains a diverse assemblage of invertebrate trace fossils. Horizontal grazing trails, burrows of various orientations and sizes, and trilobite traces are all well-documented. The finer-grained sediments of the Bright Angel Shale provided an excellent medium for preserving these delicate traces of Cambrian life, offering insights into the feeding strategies and locomotion of early marine organisms.

.

Muav Limestone (Cambrian)

The underlying Muav Limestone (Cambrian), another significant marine limestone formation, similarly yields primarily invertebrate trace fossils. Horizontal burrows (e.g., Planolites) and vertical burrows (e.g., Skolithos) are common, indicating the presence of early worms and other soft-bodied organisms that colonized the Cambrian seafloor. Trilobite trackways (e.g., Cruziana) and resting traces (e.g., Rusophycus) are also found, providing direct evidence of the movement and behavior of these iconic Cambrian arthropods. The Muav’s trace fossils offer a glimpse into the early diversification of animal life in the marine realm.

.

Temple Butte Fm (Devonian)

Although the Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian is essentially absent in the Grand Canyon region, it exists with thicknesses over 6,000 feet in Northern Utah and Nevada. The Temple Butte (385mya) is found only in paleo channels carved out in the underlying units and is largely unfossiliferous. But elsewhere in Utah and the world, the Devonian holds the first evidence of fossilized intact growing trees. Once again showing that these units are not part of some catastrophic flood, but sediments deposited under relatively uniformitarian conditions.

.

Redwall Limestone (Mississippian)

The Redwall Limestone (Mississippian), a massive cliff-forming unit deposited in a shallow marine environment, is primarily known for its body fossils of marine invertebrates. However, trace fossils are also present, albeit less conspicuous. Burrows of marine worms and other infaunal organisms are commonly found within the limestone beds, reflecting the activity of creatures living on and within the ancient seafloor. Crinoid holdfast attachment scars can also be considered a type of trace fossil, indicating where these stalked echinoderms were anchored. While large vertebrate tracks are absent, the Redwall’s trace fossil assemblage provides evidence of a thriving benthic community in a relatively stable marine environment.

.

Surprise Canyon Formation (Mississippian)

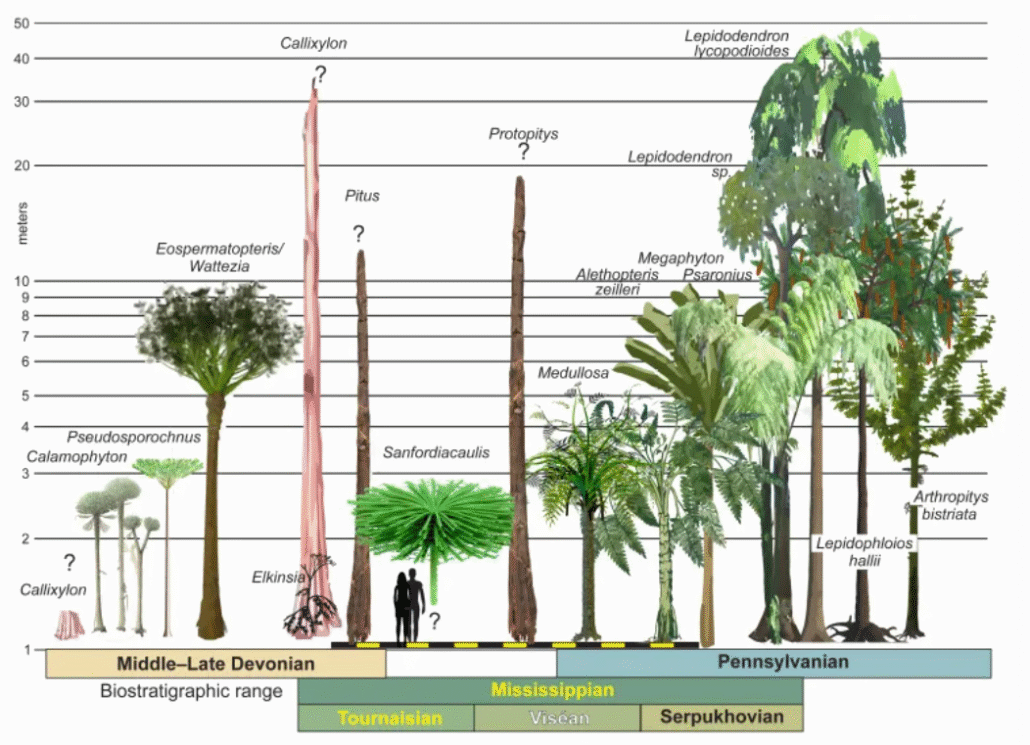

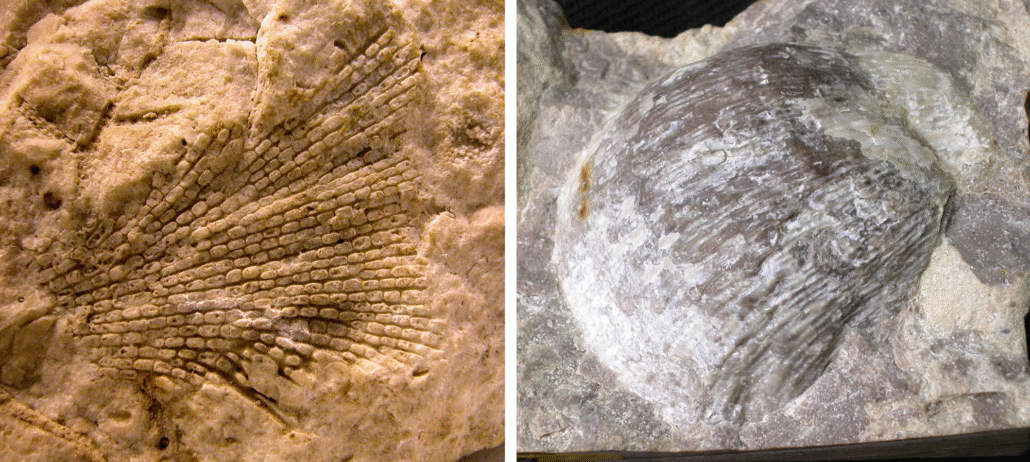

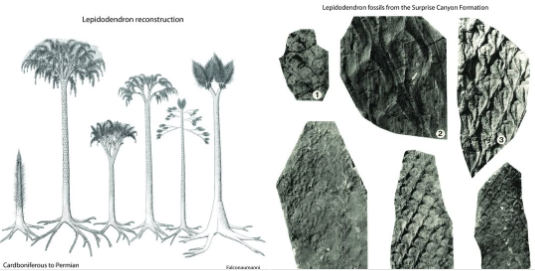

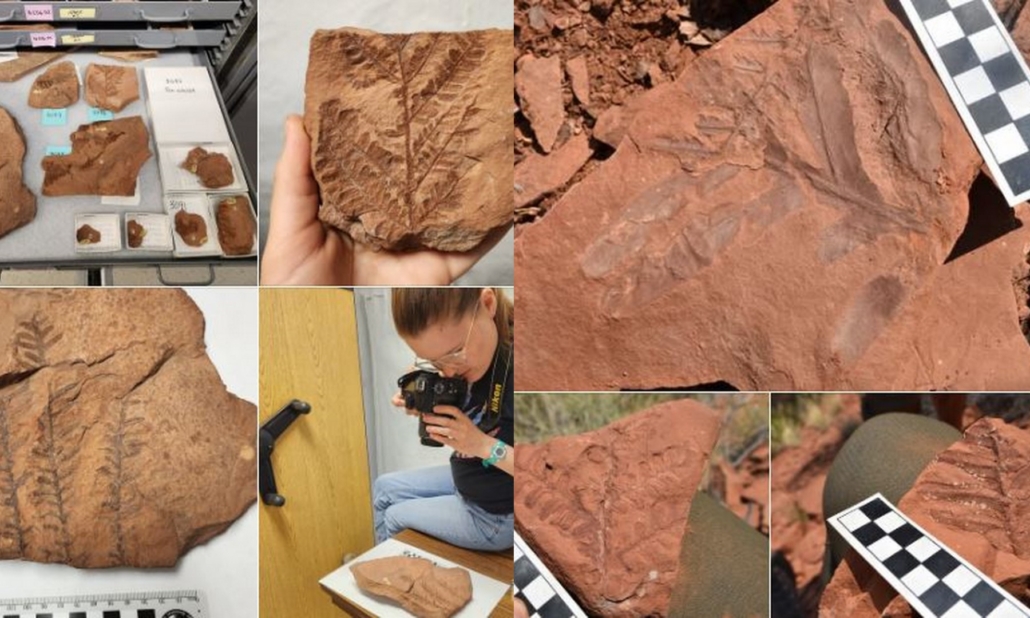

Hidden in small paleochannels carved into the Redwall Formation lies the Surprise Canyon Formation. Before the seas rose and formed an estuary full of sharks and invertebrates, the karst features on top of what is now the Redwall Limestone were filled with rivers and streams. These streams created a lush riparian environment teeming with plants, and not just small shrubs either. Some of these plants belong to the extinct genus Lepidodendron, which were large tree-like plants that grew in wetland environments and reached heights up to 160 feet (50 meters)! Lepidodendron are often known as “scale trees” because of the distinctive diamond shaped pattern of leaf scars along its trunk. Young Lepidodendron plants form a single unbranched trunk with numerous leaves attached to the diamond-shaped bases, and only formed a crown of branches once they neared the end of their lifespan. These trees thrived during the Carboniferous Period and became extinct at the end of the Permian Period.

.

Supai Group (Pennsylvanian-Permian)

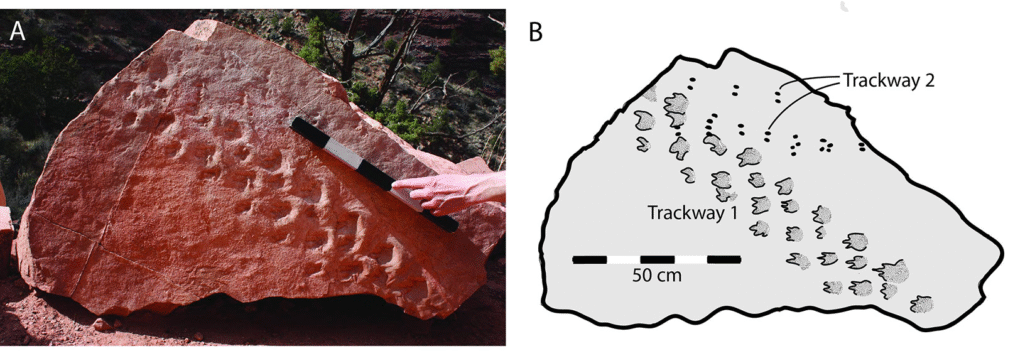

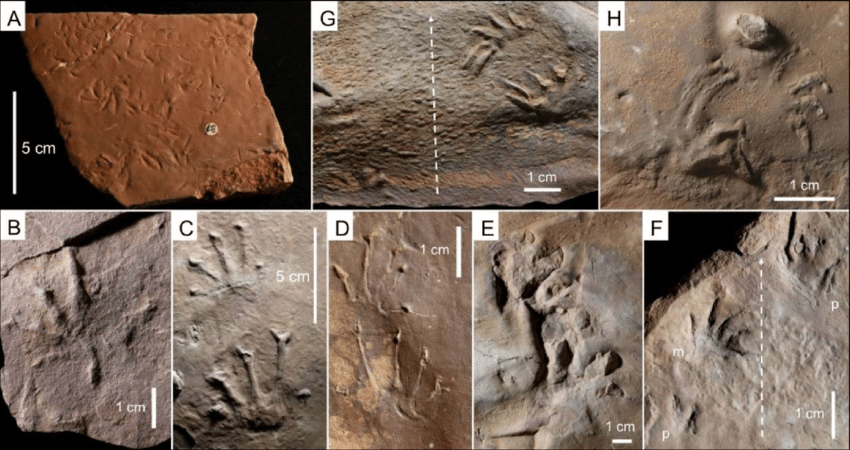

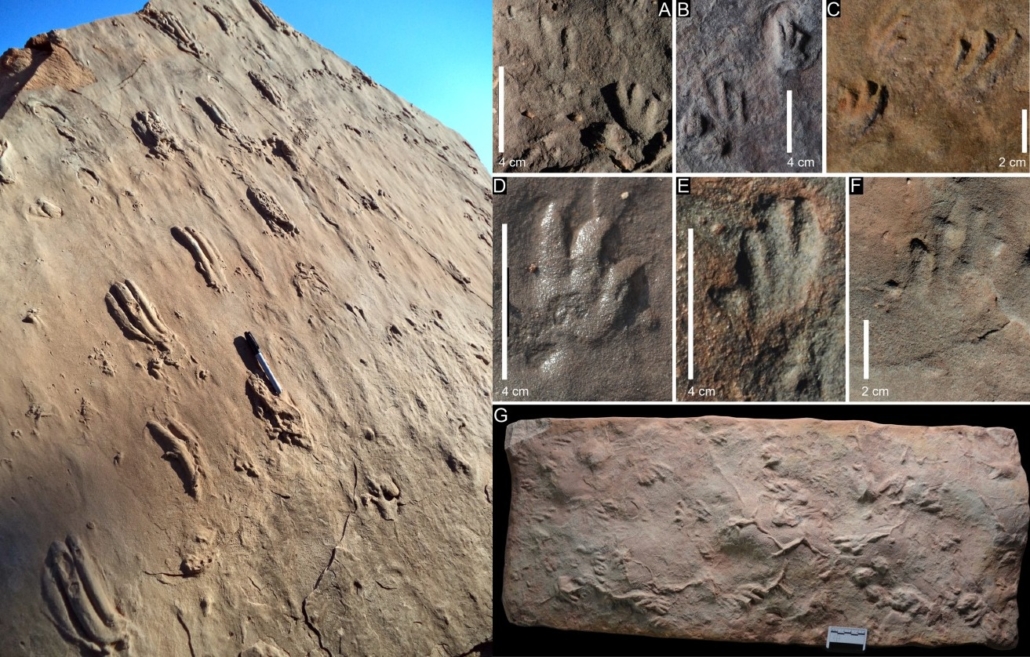

Continuing our descent, the Supai Group (Pennsylvanian-Permian), a thick sequence of sandstones, siltstones, and mudstones deposited in a variety of fluvial, deltaic, and marginal marine settings, reveals an even greater diversity of ichnofossils. Within its various members (e.g., Wescogame, Esplanade, Watahomigi, Manakacha), numerous tetrapod trackways have been discovered, representing a transitional fauna from amphibians to early reptiles. Ichnogenera such as Baropezia, Notalacerta, and various amphibian trackways attest to the presence of diverse terrestrial vertebrates along ancient shorelines and floodplains. Furthermore, the Supai Group is rich in invertebrate trace fossils, including a wide array of burrows (vertical and horizontal), trackways, and feeding traces. These indicate the presence of worms, arthropods, and possibly early mollusks inhabiting both terrestrial and aquatic environments. The varied depositional environments of the Supai Group have preserved a complex tapestry of ancient life and behavior.

While the Watahomigie Formation of the Supai Group was being deposited in the Grand Canyon, conifer forests were growing and being buried and fossilized in the Eastern US & England. In fact much of Europe and North America’s substrate trees and minable coal mines come from the ‘Carboniferous Period’ (Mississippian and Pennsylvanian 360-300 mya). This is speculated to be caused by major ice-age induced sea level changes at the time. In Utah and the Grand Canyon region however, most coal is found in the Cretaceous period. Nearly 200 million years later. Why? Likely because by that time the climate in Utah was now similiar to that in England/New England of the Carboniferous, and once again sea level was rapidly changing.

.

.

Hermit Formation (Permian)

The transition to the underlying Hermit Formation (Permian) marks a shift towards a more fluvial (riverine) and lacustrine (lake) environment, evidenced by its interbedded sandstones, siltstones, and shales. The ichnological record of the Hermit Formation reflects this change, showcasing a broader range of trace fossils. Tetrapod trackways, though perhaps less ubiquitous than in the Coconino, are still present, indicating continued habitation by early reptiles and amphibians. However, the Hermit is particularly notable for its insect trackways and resting traces, providing rare glimpses into the activity of terrestrial arthropods of the Permian. Delicate trails and impressions left by insects crawling across soft sediment have been documented, offering a unique perspective on the terrestrial invertebrate fauna of this period. Additionally, burrows and trackways of aquatic invertebrates are found in the finer-grained sediments, reflecting the presence of ancient waterways and lakes.

.

Schnebly Hill Formation (Permian)

The Schnebly Hill Formation is primarily exposed in the Sedona area along the western Mogollon Rim (50 miles south of the Grand Canyon). It consists of cross-bedded sandstones, mudstones, limestones, and evaporites deposited in a mix of eolian, coastal, and shallow marine environments within the Holbrook Basin. It sharply overlies the Hermit Formation (or Hermit Shale) in the Sedona region and intertongues upward with the Coconino Sandstone, reaching thicknesses of 300–600 m eastward but thinning westward to the point of pinching out just east & south of the Grand Canyon. (But still occupying a time period between the Coconino Sandstone and Hermit Formation. It contains many impressive marine & terrestrial fossils, as well as track sites.

.

Coconino Sandstone (Permian)

Beneath the Toroweap lies the striking Coconino Sandstone (Permian), a massive cross-bedded sandstone representing an extensive ancient sand sea (erg). This formation is renowned for its exceptional preservation of tetrapod trackways. The fine-grained, wind-deposited sands acted as an ideal medium for recording footprints, which were subsequently buried and lithified. Numerous track sites within the Coconino have yielded a rich diversity of ichnogenera, including Chelichnus, Dromopus, Laoporus, and Octopusoides. These trackways provide invaluable insights into the gait, size, and behavior of early reptiles and possibly synapsids (the lineage leading to mammals) that navigated these ancient dunes. The consistent direction of many trackways suggests prevailing wind patterns, further painting a vivid picture of this Permian desert environment. While invertebrate traces are less common in the dominant eolian facies, evidence of burrowing organisms can be found in interdune or wetter intervals. The Coconino stands as a global benchmark for understanding early terrestrial vertebrate locomotion.

.

Toroweap Formation (Permian)

Descending through the Toroweap Formation (Permian), a transitional unit representing fluctuating marine and terrestrial influences, the ichnological record begins to diversify. The Whitmore Wash Member, often considered a temporal equivalent to the Coconino Sandstone, exhibits abundant trackways of tetrapods. These footprints, often preserved in fine-grained sandstones and siltstones, reveal the presence of early reptiles and amphibians traversing dune-like environments or marginal marine flats. Genera like Chelichnus and Dromopus, characteristic of early amniotes, have been identified, providing crucial evidence of the fauna inhabiting this transitional landscape. Additionally, invertebrate traces such as burrows and trackways continue to be found, reflecting the persistence of benthic communities in the changing environments. Aside from the Whitemore Wash Member/Coconino, the Toroweap Formation is comparatively unfosiliferous, with fossils limited to invertebrates in a few limestone horizons and the trackways of the Whitmore wash.

.

Kaibab Formation (Permian)

At the canyon’s rim, the Kaibab Formation (Permian), a resistant limestone deposited in a shallow marine environment, might seem an unlikely place for abundant tracksites. However, careful examination reveals evidence of invertebrate activity. Trace fossils such as burrows (e.g., Planolites, Palaeophycus) and grazing trails are documented, indicating the presence of worms and other soft-bodied organisms that moved through the muddy seafloor. While large vertebrate tracks are less common in the main canyon exposures of the Kaibab, equivalent formations outside the immediate Grand Canyon region have yielded footprints of early reptiles, suggesting the potential for future discoveries within its upper layers. The Kaibab’s story is primarily one of a marine ecosystem, its trace fossils reflecting the simple yet persistent life within those ancient seas.

.

.

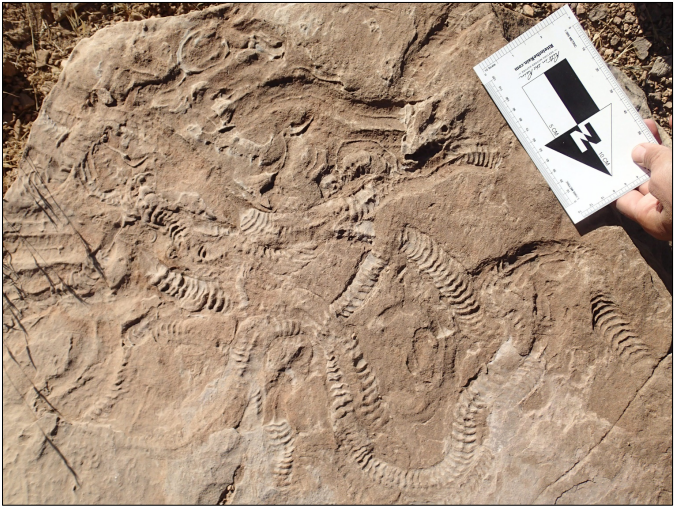

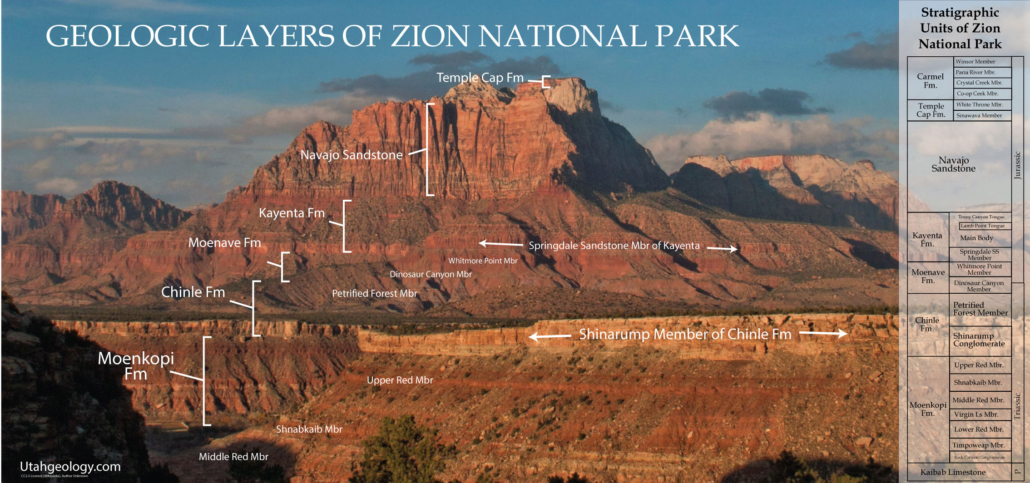

Mesozoic Layers Just North of Grand Canyon

The Moenkopi and Chinle formations which stratigraphically sit just on top (just younger) than the layers of the Grand Canyon have many, many impressive trace fossils.

Although they are very rare, Placerias fossils have been found in the Blue Mesa Member of the Chinle Formation within Petrified Forest National Park. Placerias are a type of dicynodont that lived during the Late Triassic Period. These herbivores grew to be up to 11ft long and a ton in weight with two short tusks like a boar or saber-toothed tiger. Once thought to be reptilian, complete skeletons show a far more mammal-like anatomy similar to the Therapsids of the Permian.

The fact that Therapsid-like fossils as big as Postosuchus (shown below) appear as early as the Chinle in the Late Triassic shows either how quickly things diversified after the Terminal Permian Extinction or that many unknown clades lived before and then through the extinction. Desmatosuchus (on the right) was a large crocodile-like reptile measuring 15 – 16 ft long and weighing about 620–660 lb.

Although true ‘dinosaur’ footprints don’t exist in the Grand Canyon or any Grand Canyon aged (Paleozoic) layers, numerous dinosaur track sites exist in the slightly younger Mesozoic layers just north of the Grand Canyon region. One of the best might be the Dinosaur Discovery Site (tracksite museum) at Johnson Farm in St George, Utah about 70 miles north of the Grand Canyon. (you can explore the museum 100% virtually at this link)

.

.

.

Cenozoic Layers Just East of the Grand Canyon

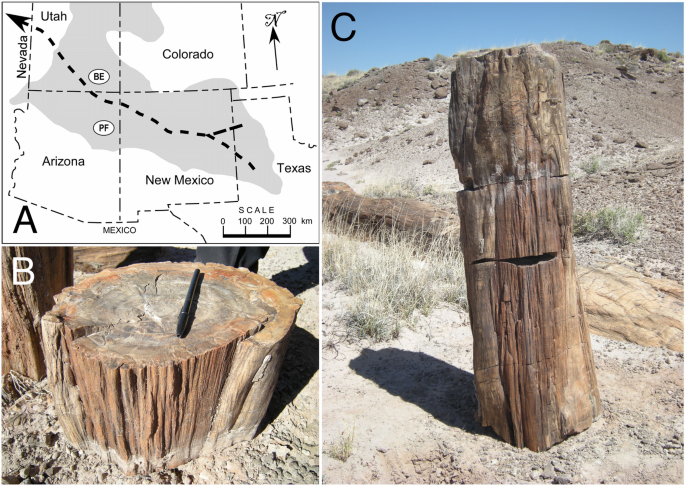

The San Juan Basin, 200 miles east of Grand Canyon, hosts some of the best in situ (in place) petrified logs in the west, dating from 120-55 million years ago. The Fossil Forest member of the Fruitland Formation. Ah-She-Sle-Pah Wash, New Mexico. Great examples can be seen on the phototreknm.com page as well as the AMAZING photographic journey of Peter & Tanja at https://wilde-weite-welt.de

In Situ Petrified tree from the Ah-Shi-Sle-Pah Wilderness, New Mexico (About 200 miles East of the Grand Canyon in the Nacimiento Formation? 65mya, see here)

On the Grand Staircase, by far the best units to find petrified trees (in ancient river systems) are the Triassic Chinle and Jurassic Morrison Formations. Both of these units are easily discernable ancient river systems.

The immense number of fossils found in the Eocene Green River formation might lead some to suppose some type of catastrophic event led to the death and burial of so many animals, but as seen in the next image, numerous trace fossil burrows and trackways prove a fairly uniformitarian habitat existed in this large inland lake. Although it seems likely that the lake somehow became toxic during episodes, perhaps like the Aerial Sea of Asia or Lake Turkana of Africa where massive changes in ph coinciding with large influxes of sediment played a part in their demise.

Ice age magafauna such as the Huntington mammoths & groundsloth found on the Wasatch Plateau near Price, Utah during construction of the Huntington damn project. These animals are often found on the top of the stratigraphic column. The Huntington fossils were found in a bog sitting on glacial outwash radiocarbon dated to around 12,000 BP. The outwash sites on top of Paleocene Northhorn Formation, however, many tusks and teeth have been found in Lake Bonneville Shoreline deposits which date from Miocene to Pliestocene in age. Hair and skat has been found in Navajo Sandstone coves in Glen Canyon just up river from the Grand Canyon.