Historic Great Salt Lake Levels & Colorado River Water Scarcity (& How They Lie to You)

How They Lie to You

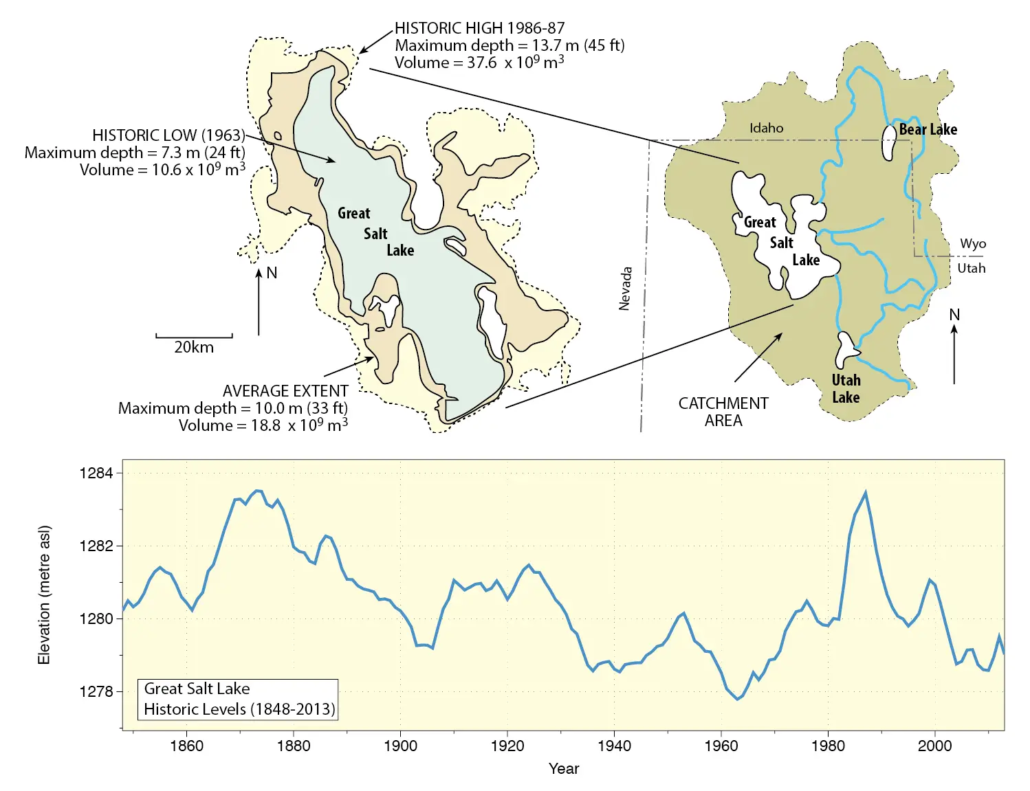

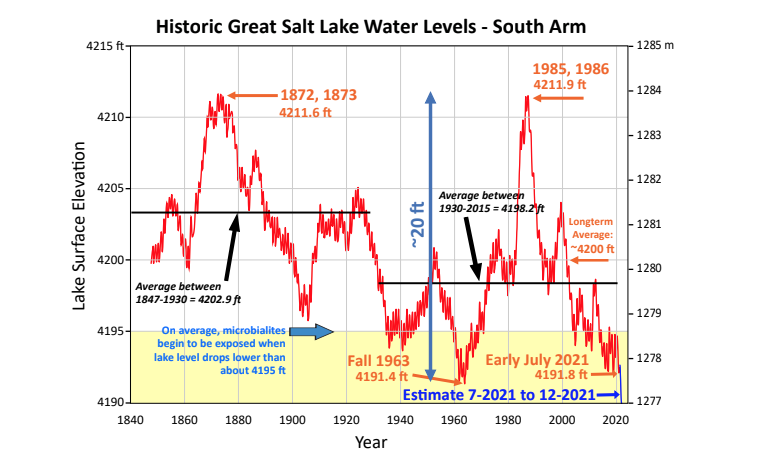

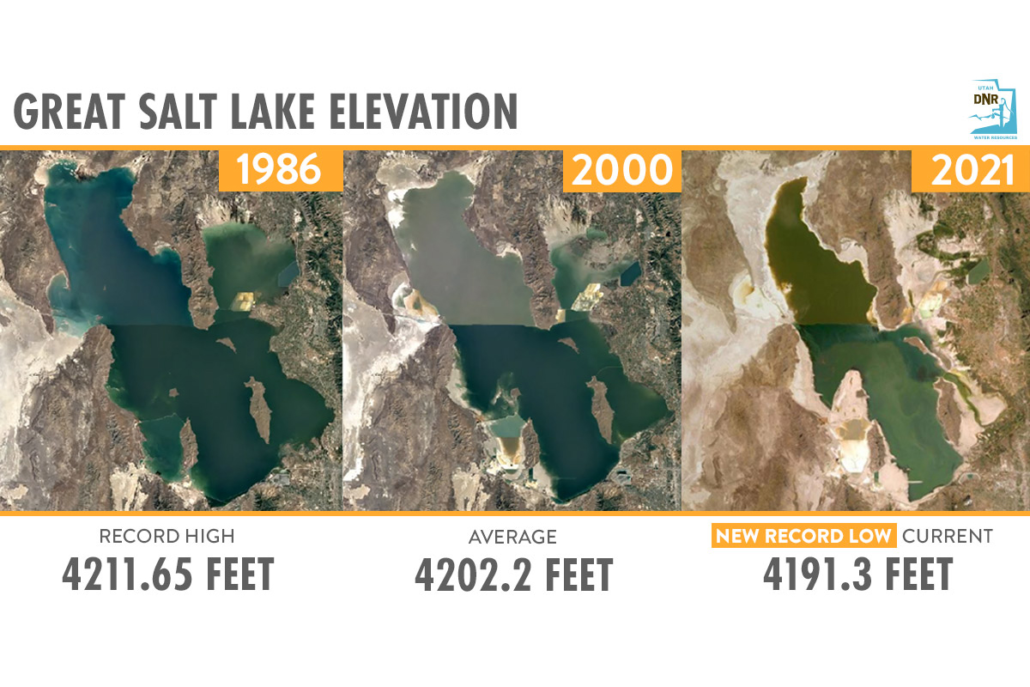

Recently the New York Times did an article on the Great Salt Lake, titled “The Great Salt Lake Is Drying. Can Utah Save It?” In this piece of propaganda disguised as a scientifically based article, they showed a chart of “historic levels of the Great Salt Lake”, which misleadingly started in 1980’s at the lakes historic high stand and ended in the present levels. The chart, much like the article purposefully left off any mention of how lake levels just a few decades prior to the 1980’s were just as low as those today. Misleading uninformed readers into thinking climate change had caused some sort of unprecedented crisis. I was informed of this article by several worried readers, who bought the propaganda and wondered what was to be done? As a start, I want to share the following information to decisions can be based on a balanced view of the past instead of propaganda.

Statistical Overview

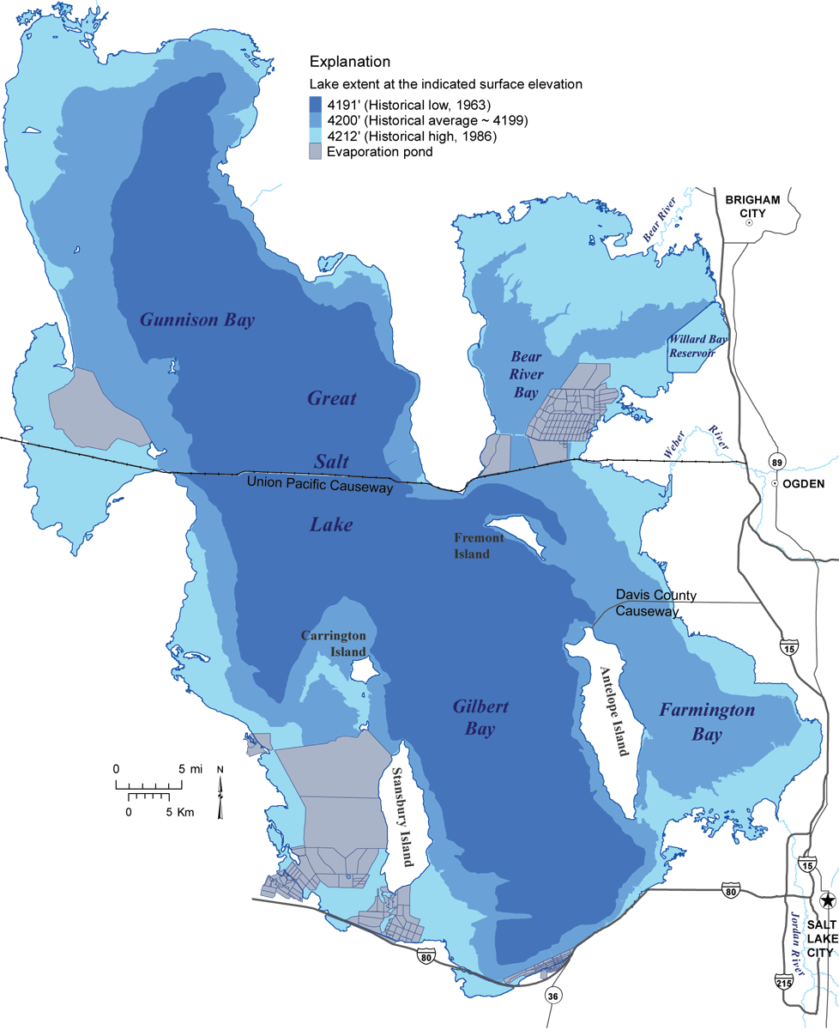

The Great Salt Lake, located in the northern part of the U.S. state of Utah, is the largest saltwater lake in the Western Hemisphere and the eighth-largest terminal lake in the world. As a terminal lake, it has no outlet; water leaves only through evaporation, leaving behind concentrated minerals and salts. It is a remnant of the prehistoric Lake Bonneville, which at its peak covered roughly 20,000 square miles of western Utah and reached depths of 1,000 feet.

Today, the statistics of the lake are as fluid as its shoreline. While its average surface area is approximately 1,700 square miles, this figure can vary by thousands of miles depending on the water level. The lake is remarkably shallow, with an average depth of only about 14 to 15 feet. Its salinity ranges from nearly fresh at the river inlets to roughly 27% in the North Arm—nearly nine times the salinity of the world’s oceans.

Historical Hydrology and the 1960s Baseline

The history of the Great Salt Lake is defined not by stability, but by dramatic, oscillating cycles. Since formal record-keeping began in the mid-19th century, the lake has been a barometer for the climate of the Intermountain West. Contrary to modern narratives that suggest a linear decline, the historical data shows a series of “low-water” events followed by massive recoveries.

In the mid-1860s, early settlers and explorers noted significantly low levels as the region experienced a period of prolonged aridity. By the early 1900s, specifically around 1905, the lake again dipped to concerning levels that prompted local discussions about the lake’s potential disappearance. However, the most significant historical benchmark occurred in the 1960s. In 1963, the Great Salt Lake reached what was then its lowest recorded level in history, dropping to an elevation of approximately 4,191.35 feet above sea level.

At that time, much like today, there were fears that the lake was in a terminal state of recession. Yet, only twenty years later, the cycle reversed with unprecedented ferocity. By the mid-1980s, the lake rose so rapidly and so high (reaching 4,211.6 feet in 1986 and 1987) that it caused hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to infrastructure, railways, and interstate highways, necessitating the construction of the multi-million dollar “West Desert Pumping Project” to move excess water out of the basin.

Sensationalism vs. Historical Fluctuations

In recent years, the Great Salt Lake has again reached levels that match or slightly exceed the lows of 1963. While this is a significant hydrological event, the framing of these levels by modern media outlets and environmental organizations often borders on the sensational. By focusing exclusively on a 20- or 30-year window, these outlets frequently present current conditions as “unprecedented” or a “looming collapse” that has never occurred before.

This narrative often ignores or deliberately obscures the fact that the lake has reached these exact depths multiple times in the last 160 years. When organizations with specific political or environmental agendas present the current low levels as a permanent “new normal” caused by irreversible factors, they overlook the demonstrated historical resilience of the basin. The history of the lake proves that “record lows” are not the end of the story, but rather a recurring phase in a long-term hydrographic cycle. By creating a culture of fear, these groups often attempt to bypass nuanced discussions about water management in favor of radical policy shifts, hiding the reality that the lake has always recovered from these cycles in the past.

The Great Salt Lake as a Colorado River Proxy

The Great Salt Lake serves as one of the most reliable and carefully measured proxies for determining the historical and future flows of the Colorado River. Because both the Great Salt Lake Basin and the Upper Colorado River Basin rely on the same primary water source—the winter snowpack of the Rocky Mountains—their hydrological fates are intrinsically linked.

For decades, the same organizations that sensationalize the levels of the Great Salt Lake have applied the same tactics to the Colorado River. The public is often told that the Colorado River is in a state of terminal decline and that reservoirs like Lake Mead and Lake Powell will never again reach capacity. The narrative suggests that the “megadrought” is a permanent shift in the planetary climate that renders historical data irrelevant.

However, the Great Salt Lake suggests otherwise. The lake’s long-term data provides a clear record: periods of extreme low flow and low lake levels are inevitably followed by periods of high precipitation and rapid recovery. If the Great Salt Lake could transition from the “all-time record low” of 1963 to the “all-time record high” of 1987 in just over two decades, it demonstrates that the Intermountain West’s water systems are characterized by high-amplitude volatility, not linear exhaustion.

The Great Salt Lake stands as a physical rebuttal to the claim that current low levels in the Western water systems are unprecedented or final. Just as the lake “disappeared” in the 1860s, 1905, and 1963 only to return with a vengeance, the hydrological history of the region suggests that the Colorado River flows will eventually follow the same path of recovery. The lake is a reminder that in the West, the only constant is change, and the most dangerous mistake a researcher can make is to mistake a cyclical low for a terminal end.

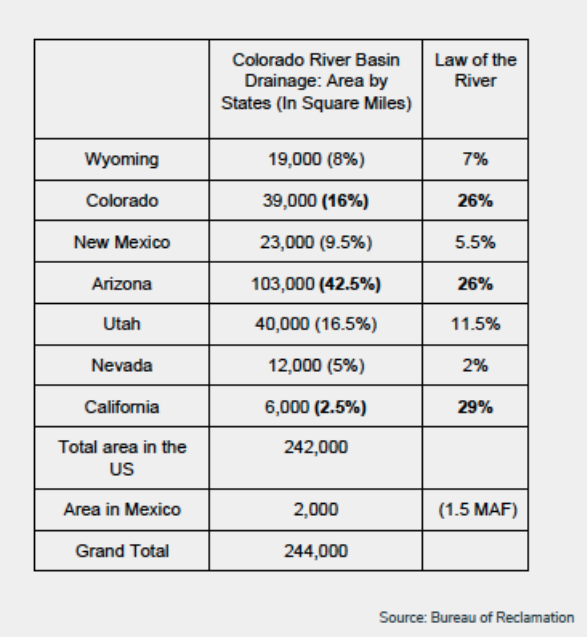

How Utah is Getting Screwed Out of Its Colorado River Allocation

Despite the cyclical resilience of the region, Utah is currently allowing itself to be cheated out of its rightful annual allocation of the Colorado River. This systemic loss is driven by a fundamental failure in water accounting: the state fails to properly calculate and credit the “return flows” of water used in its diversions. In the rigid accounting of the Colorado River Compact, Utah is often charged for the total volume of water diverted, rather than the “consumptive use” which represents water actually lost to the system. This ignores the reality that a significant percentage of water used for irrigation or municipal purposes eventually returns to the river system via surface runoff and groundwater recharge, effectively subsidizing the lower basin states at Utah’s expense.

The physical data supports the conclusion that Utah’s actual footprint on the river is far smaller than administrative figures suggest. According to a 2024 study published in Nature (“A database of all major water diversions in the Upper Colorado River Basin“), there are 1,358 major water diversions in the upper river system. Of these, Utah accounts for only 101—the vast majority of which are concentrated on reservation lands in the Uinta Basin. It is hydrologically improbable that these few, localized diversions are permanently removing the massive volumes of water currently calculated in the state’s usage reports. The state is being held to a standard of “permanent withdrawal” that fails to account for the cyclical return of that water to the downstream flow.

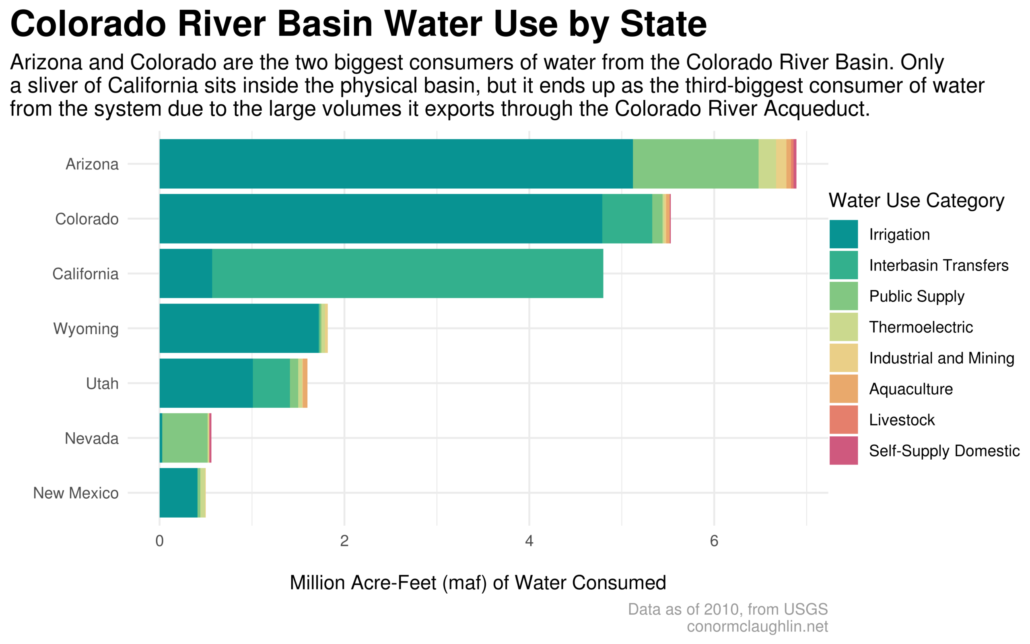

Furthermore, a comparison of irrigated agricultural land across the basin states reveals a stark imbalance between supposed usage and actual land footprint. While California and Arizona manage millions of acres of intensive, year-round agriculture within the basin, Utah’s irrigated acreage in the Colorado River basin is a mere fraction of that scale. The stats simply do not add up: Utah is credited with using a disproportionate amount of its allocation despite having significantly fewer diversions and less irrigated land than its neighbors. By accepting these flawed metrics, Utah is forfeiting its water security to feed a narrative of scarcity that ignores the basic mathematics of its own land use and hydrological return.

Comparative Water Use and Land Footprint

The following table illustrates the disparity between water contribution, administrative withdrawal figures, and the actual agricultural land footprint within the Colorado River Basin.

| State | Water Contribution (Acre-Feet/yr) | Total SUPPOSED Withdrawal (Acre-Feet/yr) | Agricultural Use (Acre-Feet/yr) | Irrigated Acreage (In-Basin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorado | ~9,100,000 | ~2,500,000 | ~2,250,000 | ~1,500,000 |

| Utah | ~1,400,000 | ~1,000,000 | ~850,000 | ~300,000 |

| Arizona | ~500,000 | ~2,800,000 | ~2,100,000 | ~900,000 |

| California | 0 | ~4,400,000 | ~3,800,000 | ~900,000 |

| Nevada | ~25,000 | ~300,000 | ~15,000 | ~5,000 |

Data represents generalized annual averages to illustrate the scale of disproportionate use vs. land footprint.

By accepting flawed metrics that ignore return flows and localized land footprints, Utah is forfeiting its water security to feed a narrative of scarcity that ignores the basic mathematics of its own land use and hydrological return.

[under construction: helping people see that it is over-allocation to lower basin states NOT any type of long term, unprecedented climate crisis that is causing scarcity in the Colorado River.]

.

.

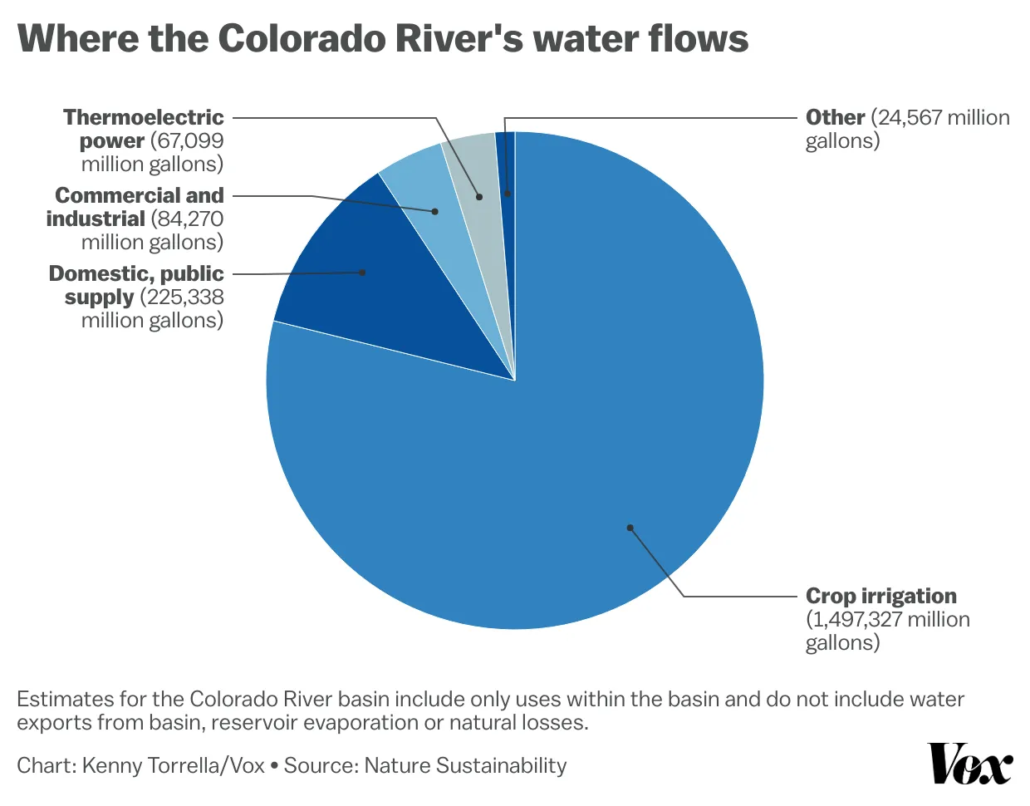

Colorado River Statistics: (NOTE 70% OF COLORADO RIVER WATER IS USED FOR CROP IRRIGATION!)

About the Colorado River

- The Colorado River:

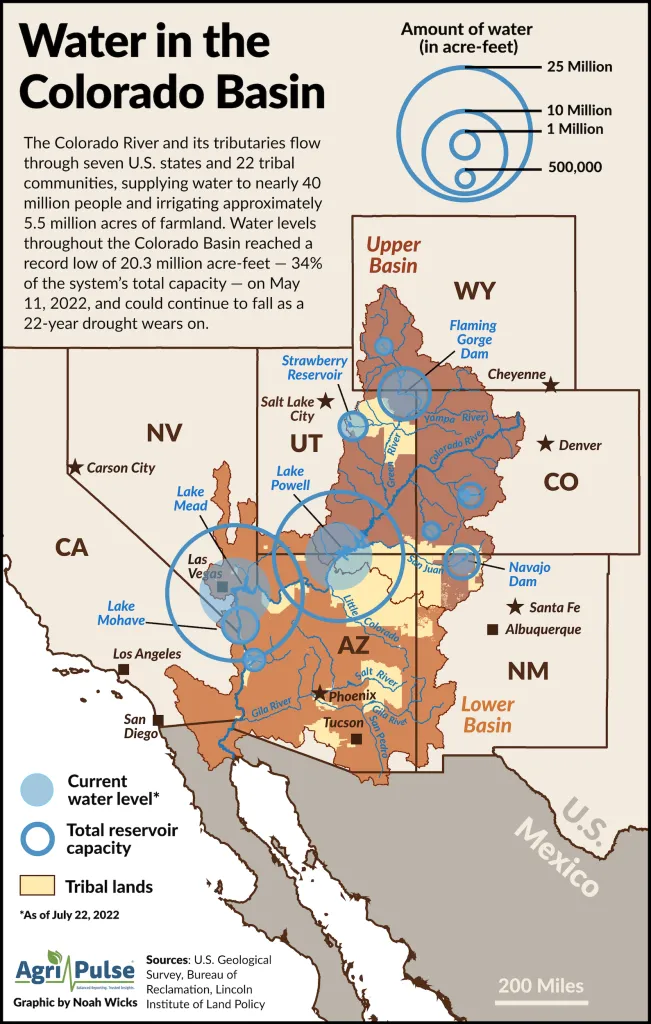

○ supplies water to 40 million people in the U.S. and Mexico;

○ irrigates nearly 5.5 million acres of land; and

○ is a water source for 30 federally recognized Tribes. - Nearly 70% of Colorado River water use is for agriculture

- The Colorado River basin (“basin”) is divided into an Upper and Lower Basin at Lee Ferry, AZ.

- The Upper Division States of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming receive Colorado River

water, as do the Lower Division States of Arizona, California and Nevada (collectively, the “Basin

States”). - Nearly 90% of Colorado River water originates in the Upper Basin.

- The Colorado River is approximately 1,400 miles long and the basin is approximately 250,000

square miles. - The “Law of the River” refers to the body of laws, regulation and policy that governs Colorado

River operations. - The 1922 Colorado River Compact (“1922 Compact”) is the cornerstone of the Law of the River.

The River’s Track Record - The Colorado River system has experienced frequent cycles of drought and recovery throughout

its history. - Although Colorado River hydrology has been impacted by drought and climate change since

2000, over the past century the river, together with storage, have provided sufficient water in

both wet and dry cycles to meet established uses and compact requirements. - The Upper Division States have historically supplied and received credit for Colorado River flows

to the Lower Basin in excess of their 1922 Compact obligations.

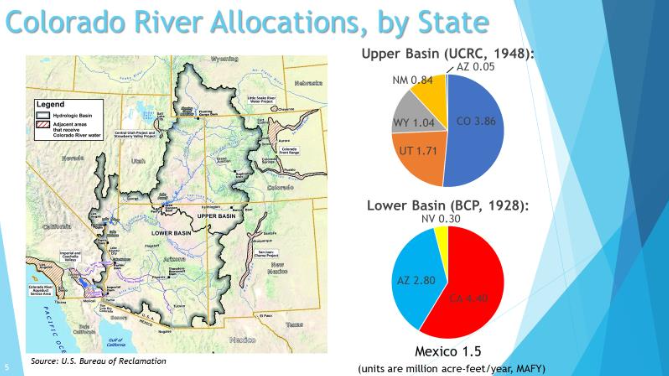

Allocations and Obligations

Basin States - The primary purpose of the 1922 Compact is “to provide for the equitable division and

apportionment of the use of the waters of the Colorado River System.”3 - The compact allocates the exclusive beneficial consumptive use of 7.5 million acre-feet of water

annually to each basin.

o 1928 Boulder Canyon Project Act allocated to each Lower Division State a fixed portion

of the Lower Basin’s apportionment - 1948 Upper Colorado River Basin Compact (“1948 Compact”) apportions to each Upper

- Division state a fixed percentage of the supply available to the Upper Basin in any given

- year and 50,000 to the state of Arizona.

- The 1922 Compact provides that the “States of the Upper Division will not cause the flow of the

river at Lee Ferry to be depleted below an aggregate of 75,000,000 acre-feet for any period of

ten consecutive years (the “non-depletion obligation”). - The 1922 Compact also provides that “present perfected rights to the beneficial use of waters of

the Colorado River system are unimpaired by this compact.”8 - In the event the Upper Basin cannot meet its non-depletion obligation under the 1922 Compact

and curtailment of Upper Basin uses becomes necessary, the extent of curtailment by each

Upper Division state shall be in the quantities and at the times determined by the Upper

Colorado River Commission in accordance with the 1948 Compact. - Each state will then determine how water users subject to its jurisdiction will be required to help

meet the state’s curtailment obligation - Utah will administer curtailment within the state in accordance with Utah law and under the

regulation of the State Engineer.

Mexico - The United States committed 1.5 million acre-feet of the river’s annual flow to Mexico under the

1944 Mexican Water Treaty. - The 1922 Compact also requires satisfaction of Mexico’s Treaty entitlement.

Tribal Water Rights11 - Tribal water rights are assessed against the Colorado River apportionment of the state in which

the Tribe’s lands are situated.

Developing River Water - The Lower Division States have the right to develop and beneficially use their respective

allocations of the 7.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water apportioned to the Lower Basin.. - The Upper Division States have the right to develop and beneficially use their allocated

percentages of the supply available to the Upper Basin after deducting Arizona’s 50,000 acrefeet allocation. - The compacts were expressly developed to ensure that faster growing states would not be able

to claim all available Colorado River water.

Utah’s Colorado River Allocation, Current and Future Use - The 1948 Compact allocates Utah 23% of the Upper Basin available supply

- 27% of all water used in Utah comes from the Colorado River.

- Utah’s future water plans incorporate the impacts of climate change, extended drought and

reduced natural flows in the Colorado River. - Potential future/proposed development

o Tribal water right settlements in the Upper Basin

Navajo Nation: 81,500 acre-feet (2015 Agreement and 2020 Settlement ratified

by Congress)

Ute Indian Tribe: 144,000 acre-feet (Court Decree) and potential for additional

115,000 AF (1990 Compact ratified by Congress in the 1992 Central Utah Project

Completion Act legislation and Utah. Tribe has yet to ratify)

o Municipal and Agricultural Uses

Additional municipal and industrial uses are contemplated within Utah’s

compact allocation